Jeffrey Bratberg, a clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of Rhode Island, is a member of the Governor’s Overdose Prevention and Intervention Task Force. A consultant to prescribetoprevent.org, a website devoted to opioid overdose education and naloxone training, Bratberg helps to implement, expand and study the outcomes of the Rhode Island Collaborative Pharmacy Practice Agreement and standing orders for naloxone, which arose from a partnership among the Rhode Island Department of Health, the Rhode Island Board of Pharmacy, an addiction medicine provider and a majority of pharmacies in Rhode Island.

Bratberg talked recently with Providence Business News about the Governor’s Task Force and its progress, as well as the ongoing challenges community pharmacists face regarding opioid dispensing, opioid safety, overdose and addiction.

PBN: Tell us about the Governor’s Overdose Prevention and Intervention Task Force, including its goals and objectives and progress to date?

BRATBERG: The Task Force is composed intentionally of stakeholders representing research, public health, insurance, pharmacies, professional licensing boards, addiction clinicians, recovery treatment centers, first responders, public safety officials and members of the General Assembly. Its overarching goal is to reduce the number of opioid overdoses and related emergency department visits by one-third over the next three years, through a four-part strategic plan addressing prevention, overdose response, treatment and recovery.

Since its November 2015 launch, the Task Force has made significant progress in several areas. In the prevention arena, we are nearing our goal of having 100 percent of physicians prescribing opioids enrolled in the prescription monitoring program, which is designed to reduce overprescribing of opioids. DOH Director Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott has led a national petition urging the Food and Drug Administration add a “black box” warning on all opioid and benzodiazepine medication labels warning of their dangers, and the Task Force continues to work on promoting the use of nonopioid therapies.

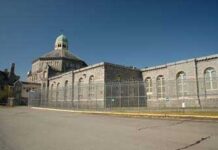

The overdose response plan aims to ensure patients have access to nalaxone as the standard of care. With thousands of prescribers and pharmacies trained in how and when to co-prescribe naloxone, the enactment of the Good Samaritan Act, expanding the quality and availability of medication-assisted treatment and access to peer recovery services, some progress is being made, but more needs to be done. Sustainable funding to provide naloxone to patients at the highest risk of overdose and their caregivers, at every possible point of interaction with the health care system – from emergency departments to the Adult Correctional Institutions to methadone clinics to substance abuse treatment centers – is essential.

PBN: Which is the more resolvable societal problem – prevention or intervention – and why; is Rhode Island allocating appropriate fiscal and human resources to the more readily solvable dilemma?

BRATBERG: The question isn’t really what’s more resolvable, but that both prevention (reductions in dangerous combinations and supplies of opioids) and intervention (overdose reversal and demand reduction via treatment and recovery service) must be performed in tandem through a comprehensive strategy that includes both. One cannot limit opioid supply via solutions such as prescribing limits, prescription drug monitoring program improvements and prescriber education without also reducing demand through naloxone education, insurance coverage, distribution, co-prescribing and proactive recommendations from prescribers and pharmacists.

It might seem best to avoid exposing more people unnecessarily to opioids when up to 10 percent of the population may have genetic and other risk factors to misuse them. However, we need to reduce the risk of unintentional harm to and death in the more than 20,000 Rhode Islanders already experiencing the diseases of substance abuse disorder. We can do this by advocating for and expanding access to evidence-based treatment with buprenorphine and methadone, seek sustainable funding to ensure that the individuals most in need – those in prison, in substance use disorder treatment programs or treated in emergency rooms for nonfatal opioid overdoses – have access to naloxone, treatment with methadone or buprenorphine and recovery services from certified peer recovery specialists.

PBN: Your pharmacy background has informed your understanding of the challenges community pharmacists face regarding opioid dispensing, opioid safety, overdose and addiction. What are those challenges and what is the best way to overcome them?

BRATBERG: With respect to dispensing, about 10 percent of all prescriptions are opioids. This is a 400 percent increase from 15 years ago. Not all of these opioid prescriptions are issued for a legitimate medical purpose; federal regulations require pharmacists to detect and solve problems in controlled substance prescriptions before dispensing such drugs or face penalties. These penalties, limited time, incomplete medical information and lack of efficient communication with prescribers are significant barriers to detecting and solving these red flags. This leads, at times, to unintended consequences of drug diversion, drug misuse or denial of appropriate therapy to patients.

As for opioid safety, pharmacists can advise prescribers and patients about appropriate opioid regimens, nonopioid alternatives and, for those with increased overdose risks, naloxone. Although they can also recommend storage lockboxes for and safe disposal of opioids, most pharmacies don’t offer onsite disposal and lack of insurance coverage for lockboxes are both barriers to implementing comprehensive safety measures.

Screening patients for risk factors for opioid overdosing is challenging, as most pharmacy and clinical information systems do not provide alerts. Pharmacists’ attitudes on addiction reflect societal norms that regard substance abuse disorder as one of the most stigmatized diseases in existence. However, as pharmacists become increasingly recognized as care providers and public health specialists, I believe that they will lead society to recognize that individuals with substance use disorders have chronic diseases requiring medication management services.

PBN: Are those who need naloxone able to access it easily? If not, what do you attribute that to – lack of easy access 24/7, cost, inadequate supplies, reluctance of pharmacists to offer it, stigma or something else?

BRATBERG: Rhode Islanders have the greatest access to naloxone via hundreds of community pharmacies that employ pharmacists trained to provide overdose prevention and counseling. But stigma, low dispensing volume and lack of public awareness contribute to inadequate community levels of naloxone needed to bend the overdose epidemic curve toward fewer overdoes and more people in treatment. Our federal grant teams, community pharmacy partners and Task Force members are focused on defining and disseminating solutions to these issues.

PBN: What are URI’s College of Pharmacy and you, in particular, doing to prepare pharmacy students to handle this issue once they enter the workforce, and what role should they play in advising their employer about this issue?

BRATBERG: We have integrated teaching opioid safety and naloxone in our pharmacy curriculum. Our students participated in the first interprofessional overdose prevention workshop for more than 500 health care professional students throughout Rhode Island to learn from people in recovery, counsel patients on naloxone and solve complex patient cases. In addition, several student pharmacists participated in a national poster contest to increase naloxone awareness; others engage Rhode Island pharmacists to increase their recommendations of naloxone to patients with risk factors for overdose (high dosage regimens and dangerous opioid combinations). I trained more than 300 student pharmacists and faculty about nalaxone education and administration at a national pharmacy conference. I advocate that student pharmacists who work for employers that haven’t yet trained their pharmacy staff about naloxone’s benefits should work with their employer, department of health and/or their pharmacy associations to expand public access to naloxone through all pharmacies.