With a value of $698.1 million, Providence Place mall occupies a unique position in the capital city. It is at once its largest, most valuable commercial property. It also holds its most generous taxpayer subsidy, a 30-year deal that shields it from paying property and tangible taxes.

Initially aimed at a high-end market, the urban mall re-established downtown Providence as a walkable shopping destination. Current downtown business and building owners who remember Providence of the 1980s and 1990s say it helped foster a healthier environment for development that eventually resulted in the conversion of empty office buildings into modern apartment buildings.

But for a financially stressed city that is trying to grow its tax base, the discount held by the mall since it opened in 1999 has long prompted second-guessing.

Is it too generous and does it disfavor other commercial enterprises that are paying a full tax load, in a city that already has a large proportion of properties held by nonprofits?

Eighteen years after the mall changed the city’s commercial and retail landscape, what kind of return has Providence gotten on its investment?

‘IT CREATED AN ECOSYSTEM’

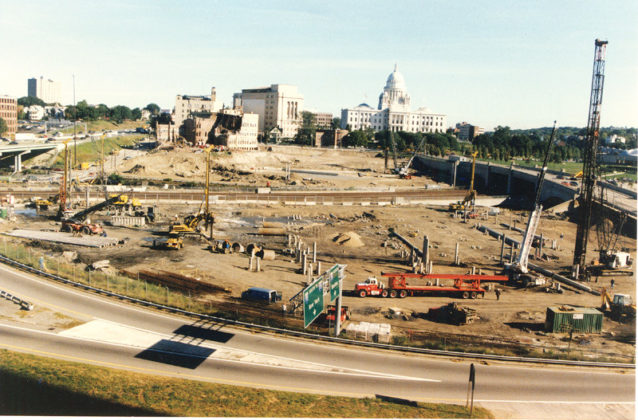

Built on a difficult site, on land divided by a river, the mall replaced facilities occupied by the University of Rhode Island and Amtrak, both government entities that paid no taxes.

It promised to generate jobs and new revenue for the city and state.

City officials tried to gauge what impact a massive urban mall would have on small, traditional retailers. The city also tried to estimate how much in taxes would be lost, into the future, based on the tax-stabilization agreement.

But according to documents on file with the city Tax Assessor’s office, both the future value of the mall and the weight of the city tax rate were substantially underestimated.

City leaders in 1995 were told the mall would be worth no more than $158.4 million before it would depreciate in value, according to a December 1995 document shared by the then-tax assessor with the City Council.

The document forecast the tax rate in fiscal 2016 at $29.97 per $1,000, or $6.78 less than it turned out to be.

Beyond the difficulties of forecasting tax rates and values 20 to 30 years into the future, critics say such long-term deals are inherently unfair because they shift the tax burden for city services to homeowners and other businesses.

City Council President Luis Aponte, among the longest serving of the council members, was not on the panel when the deal was arranged. The 30-year length of the program is unique, he said, but he wouldn’t characterize the deal as being too long or too generous, because the mall development was transformative for the city.

“It’s hard to make that judgement,” he said. “When one looks at what was there before, it created an ecosystem, a climate for development.”

The current administration of Mayor Jorge O. Elorza, however, views the deal that led to the mall as overly generous. And it has shaped its view of how many years, and what enticements, such tax incentives should include going forward, according to Brett Smiley, the city’s chief operating officer.

The city wants the mall to succeed and be healthy, but it wants the same for other businesses, Smiley said.

“The challenge we face is there are no shortage of businesses now that are struggling to make it, and they’re paying a full [tax] load,” he said. “It’s difficult for us to continue to subsidize one business that’s had a 30-year subsidy, while another business, that maybe has the same struggle, is paying their full tax bill.”

When the TSA for the mall finally expires, the property in theory will be subject all at once to full taxation.

This is called a “cliff” by economic planners, and it is avoided in modern TSAs, which feature a phasing in of the tax burden.

The current administration takes the position that the tax arrangement will come to an end, and the owner, as well as other Providence building owners operating under TSAs, will have to start paying the full burden.

How sweet is the subsidy? Property taxes and personal property taxes on items including inventory have been largely waived. And the state’s sales tax, on items purchased by customers, has been collected but a portion of it is directed to repaying the state bonds issued to help construct the mall.

The tax deal that shields the mall from paying most of its property tax burden will continue through 2028. The tax on personal property, now $55.80 for each $1,000 of inventory and equipment, also is waived for the duration.

The mall owner instead pays a lump sum in lieu of the taxes annually to Providence, which will increase from $300,000 to $500,000 this year, according to the city Tax Assessor’s office.

Were the mall subject to a full tax, with a value of $698.1 million applied to the $36.65 per $1,000 commercial tax rate, it would be paying some $25 million this year in city property taxes.

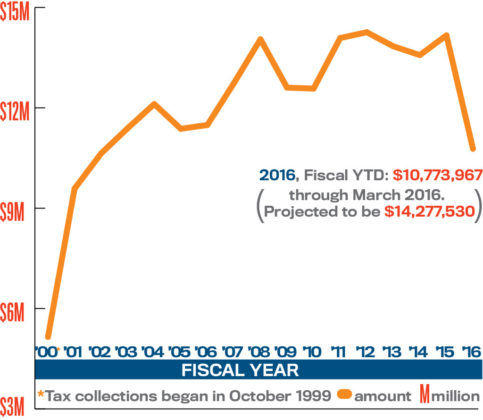

The state sales tax generated at Providence Place, which was expected to reach $14.3 million in fiscal 2016, is directed to repay the state bonds issued for its construction, as well as to the state’s general fund.

For the first five years of the mall’s operation, $3.68 million annually in sales tax was directed to the bond repayment. After that, and through June 2020, the amount decreased to $3.56 million annually, according to the state Department of Revenue.

The terms of this deal have shaped current city policy on substantial developments. The most generous offering now, for property developed in the former I-195 lands, will offer no more than a 20-year tax agreement, even for the largest, most-desirable projects.

And more current tax deals require a gradual phase-in of property tax on improvements, so the city is collecting at least some revenue from commercial development within three years of its completion.

“We continue to evolve a policy that really is the result of learning from tax lessons, both successes and failures,” Smiley said. “The mall agreement is one that most people view as probably having been excessively generous.”

A GOOD DEAL?

Mall supporters say one has to consider what the city looked like pre-Providence Place, when judging the project.

Former Mayor Joseph R. Paolino Jr. is among those who say, without question, the mall was worth it.

Decimated over time by suburban shopping centers, downtown Providence had steadily lost its retail industry by the time the mall was proposed. Westminster and Washington streets, now lively at street level, were vacant, said Paolino, now a prominent developer in the city as managing partner of Paolino Properties.

“You had nothing,” he said. As mayor, he started discussions in the mid-1980s with the original mall developer. It would take 10 years for the project to move forward, and then under a different name, and subsequent development company and mayor.

“The Providence Place mall is one of the great success stories in the renaissance of downtown Providence,” Paolino said. “There’s no ifs ands or buts about it. It’s there.”

When the deal was finally reached, Paolino was the state’s economic-development director under the late Gov. Bruce G. Sundlun. The Providence mayor was the late Vincent “Buddy” Cianci Jr. Paolino said he and Cianci flew to Seattle to sign Nordstrom, which was to become the first of the three anchors for the mall.

It is easy, with hindsight, to critique the tax strategy that helped make that happen, he said. But the mall triggered a wave of subsequent development decisions that reshaped Providence into the city it is today, he says.

“In the ’80s and the ’90s, you had a collection of development that took place, one feeding off the other,” Paolino said. “The Providence Place mall, the river relocation, the convention center, a big hotel.”

The mall also inspired other developers to buy and rehabilitate derelict office buildings and factories, in and near the downtown, he said.

“Did the city do the right thing when they moved the railroad tracks closer to the capitol? The 903 wouldn’t have been done,” said Paolino, referring to the 330-unit, midrise apartment complex constructed near the site in 2003. “The Foundry, as successful as it is today, would not have been done. We created a neighborhood. Shepard’s would still be vacant today if URI hadn’t gone there. It would be like the ‘Superman’ building.”

Before the final deal was reached, the mall had many opponents. Many worried a giant, enclosed center would destroy the city’s storefront-based retailers.

Among the opponents was Arnold B. “Buff” Chace Jr., managing director of Cornish Associates. At the time, he had tried unsuccessfully to persuade Cianci to condemn the empty, ground-level retail spaces on Westminster Street downtown, leaving the upper floors to the building owners. His idea was to create a new kind of downtown retail district, Chace said. The Gap, the national retail company, was interested in locating a store at the Peerless Building.

Providence Place put an end to all that, and compelled Cornish Associates to take a new direction, directing it away from retail and toward converting old buildings to new housing vehicles. As it turned out, that became its niche, Chace said recently, of a development pattern that is credited with attracting millennials and empty-nesters downtown.

At the time, downtown retail had evaporated. Providence was at a low point, he said.

Today, he still doesn’t think people come to the city for the mall alone, but its presence is a benefit that has made leasing his buildings easier, he said. The money for its incentives could have gone to revitalizing the existing buildings downtown, in other ways. But that wasn’t what happened. “That was the deal they struck,” he said. “The deal is what it took to get it here.”

Martha Sheridan, president and CEO of the Providence Warwick Convention & Visitors Bureau, said she can’t say whether the tax trade-off was worth the return. But the mall is a selling point for downtown Providence when bureau staff market the city to visitors, convention attendees and tour groups. The facilities are connected through an interior walkway.

A month ago, when a gymnastics tournament was held at the convention center, the preteen participants and their families made heavy use of the internal connector.

In recent years, tourism preferences have been changing, Sheridan said, and people are seeking out local, independent retailers and restaurants that reflect the city or region, such as Westminster Street or Wayland Square. But the mall has assets that continue to appeal to people who use the convention center. “Having that facility in downtown Providence has certainly enhanced our ability to sell the city to meeting and convention groups and tourism groups,” she said.

NEW DIRECTION

Since it opened in 1999, the national and regional retail landscape has changed, taking Providence Place in new directions.

The mall for the past 11 years has been among the holdings of General Growth Properties. The company, based in Chicago, has 120 properties, according to its website. The company, which is publicly traded, acquired Providence Place when it assumed the assets of the Rouse Co. It later shed many of its sites as it entered bankruptcy. The parent company exited bankruptcy in 2011.

Under General Growth management, the mix of retail tenants at Providence Place has shifted to appeal to younger, more trend-conscious customers, a redirection initiated three to four years ago after some of the original high-end retailers, such as Pottery Barn and Williams-Sonoma, departed for Garden City Center in Cranston.

In the past year, the enduring vacancy of the 116,700-square-foot space occupied by J.C. Penney Co., one of its three anchors, prompted another redirection.

The mall owner in April received permission from R.I. Commerce Corp. to replace two levels of the three-floor J.C. Penney space with parking, which will allow it to market the remaining third-floor retail space to a smaller store.

Mark Dunbar, the mall’s senior general manager, said it is aimed at young and older shoppers, and is striving for a collection of stores that will make it vibrant and attractive to the maximum number of people.

Prior to the pullout of J.C. Penney, the mall’s occupancy was listed at 97 percent, according to company papers made public in January 2015, on a municipal bond website. The mall as originally developed includes 1.2 million square feet of retail space. It employs more than 2,300 people, Dunbar said.

It is now anchored by a 200,000-square-foot Macy’s department store and an equally large Nordstrom, as well as a 16-screen cinema and the state’s only IMAX theater.

Within the past year, several new stores aimed at trend-conscious, young women and men have opened, including The North Face, Free People and Zara, a high-growth retailer that occupies a two-level, 24,000-square-foot space.

According to the most recently published Providence Place balance sheet on the Electronic Municipal Market Access website, the mall reported its assets, including building and equipment, were valued at $505.7 million as of December 31, 2014, a drop of nearly $4.5 million from the previous quarter. Of that amount, equity was reported at $93.9 million, while mortgage notes and other liabilities were listed at $411.7 million.

In the same quarter, the mall owner reported total mall revenue of $61.3 million in 2014, including $8.5 million in parking revenue.

Dunbar would not address the issue of the TSA held by the mall property. A mall spokesman, Dante Bellini Jr., said the mall owner is living up to the terms of the agreement.

UNDERVALUED

For Providence’s neighborhood retail districts, the mall is a competitor for disposable incomes of shoppers. But the individual stores are positioned differently than the mall, offering merchandise or services that can’t be found there.

Nevertheless, as small businesses, many are operating along thin lines.

Dixie Carroll, a co-president of the Hope Street Merchants Association, operates a woman’s retail store, J Marcel, that recently expanded into a second location in Rhode Island. The tax burden is heavy in Providence, she noted, and it can be difficult for small businesses to pay.

“Small-business owners feel like they’re paying more than their share,” she said.

She’s torn about the Providence Place mall, in that she wants it to remain vibrant but is competing as a retailer and paying taxes for her inventory, and through her rent, for the property itself.

She estimates she paid $1,000 last year in personal property tax for her business.

In May, when a required revaluation for the city was completed, the mall and land were valuated at $698.1 million, according to data provided by the private contractor that performed the work, Vision Government Solutions.

That represents a $52 million increase from the assessment three years ago.

Twenty years ago, as city leaders were evaluating the proposed TSA agreement with the mall-development company, officials did not see the mall increasing in value as it aged.

According to documents maintained by the Providence Assessor’s office, the city’s Finance Department in December 1995 said the land and buildings on the mall site at that time were worth $25.2 million.

Marshall Valuation Service was asked by the city to set the future value of the mall and parking garage. The company determined the mall and parking would be worth $158.4 million on completion in 1998, before depreciating over 30 years to $81.1 million in 2028. It’s not clear from city documents whether the projected value of the land was included.

Among other things, the evaluation also assumed that the tax rate would decrease by 20 percent in each revaluation year.

In 1995, the City Council was told the city would be giving up $175.8 million in taxes over 30 years, based on estimates and assumptions that appear to have understated the future value of the property, as well as the tax rate.

John Palmieri was director of planning and development for the city when the mall opened. He said at the time, Providence was an unproven market for developers.

The capital-center district, as it now exists, wasn’t there. With the benefit of hindsight, the city could have required a share of the income generated by the mall.

“I don’t think it’s unusual the city failed to consider something that would have allowed them to generate some income,” said Palmieri, who went on to lead the Boston Redevelopment Authority and who now works in Atlantic City.

“Each city does it differently,” he said.

In Providence, advocates of the mall say it has had a multiplying effect on the city’s growth, citing developments that it directly inspired, as well as the employment and sales and income taxes generated on-site.

“It’s nice to say, ‘Gee, it should have been a 20-year [tax-incentive agreement] instead of 30 years,’ but you had to know where we were,” said Paolino. “Property taxes are important, but it wasn’t the only thing.” •

PBN has confusing, poorly labeled charts.