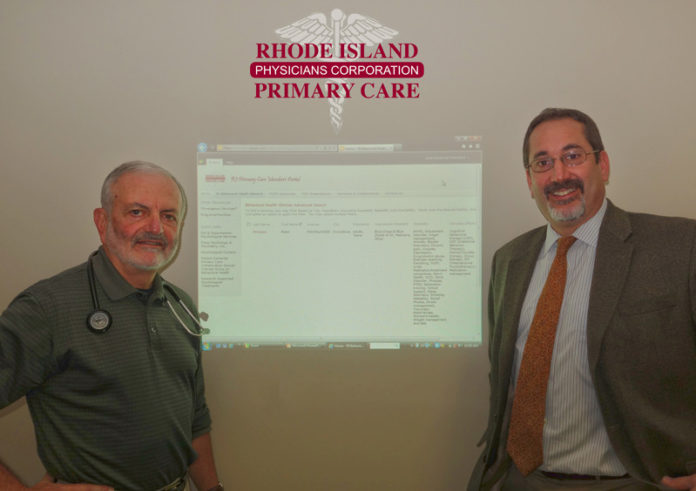

A secure, online network has been designed to help primary care doctors coordinate care confidentially with behavioral-health providers.

Dr. Albert Puerini, president and CEO of the Rhode Island Primary Care Physician Corp. in Cranston, said the Behavioral Health Network, which was created to serve – at least to start – the patients of 150 primary-care doctors in his company, took two years of research. Already in use through beta testing in October and November, it is expected to fully launch this month, said Noah Benedict, the corporation’s chief operating officer.

The direct-mail messaging technology enables primary care doctors to make referrals securely through a database of credentialed behavioral-health professionals and follow up via email with care for the physician’s patient, said Puerini.

One clinical psychologist who already has seen the benefits of the new system firsthand is Peter Oppenheimer. Based in Barrington, Oppenheimer also is president-elect for the 200-member Rhode Island Psychological Association, and will take over in 2014.

A pediatrician referred two adolescent patients to Oppenheimer, and the psychologist has met with them and begun to coordinate their care with the pediatrician by following up with email updates, instead of having to communicate by letter and phone, both of which are more time-consuming, Oppenheimer said.

“I’ve seen both kids twice, but I sent the doc notes and I will follow up,” he said. “This means when they go to see their pediatrician again, the doc knows what’s happening with the kids.”

Oppenheimer finds the network effective, so far.

“I’m excited,” he said. “It’s a way to try to help us coordinate care efficiently and practically, where the pediatricians and primary care docs work in their office doing what they do, and we do what we do, but we’re able to communicate rapidly via secure email so we can have a give and take that works much better than before. The follow-up communication is a big piece of it.”

The need for such a system is mainly clinical, Puerini said, noting that 50 percent of mental-health care occurs in a primary care provider’s office, and that primary care providers write 70 percent of psychotropic medication prescriptions and 80 percent of antidepressant prescriptions.

Those statistics come from the professional journal, “The Archives of General Psychiatry,” Benedict said.

“It’s pretty common knowledge that about 75 percent of our office visits have a significant mental-health component,” Puerini said.

All the practitioners involved – in primary care and in behavioral health – “have a need here,” Puerini added, because without this tool, they have not been able to communicate “any better with us than we have with them. Most doctors have providers they know and trust, but beyond that, you’re limited.”

The network is the first of its kind in the state, and possibly the country, Benedict said.

The way this referral system typically works is for a primary care doctor to search the database for behavioral-health providers from the computer in his office, Benedict said. The patient provides details about geographic location, insurance and medical needs and the doctor searches for providers with the appropriate medical expertise or training.

The health condition could be anything from gender identity to eating disorders or depression, Benedict said.

When some specialists are found meeting the patient’s criteria, the doctor, with input from the patient or guardians, can select a specialist. The doctor will then make the referral electronically and print out the specialist’s contact information for the patient, Benedict said.

Once the connection between a patient and behavioral-health practitioner is established, Benedict added, the primary doctor can more readily track the patient’s visits and progress with the new specialist.

Besides a username and password-based membership to the corporation, which is required for the primary-care physicians, what makes the network secure is the encrypted direct-mail messaging system, which is compliant with federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act – or HIPAA – laws, Puerini said.

All participating doctors and behavioral-health providers submit documentation of their credentials, which a committee verifies, Puerini and Benedict said.

As of early November, about a dozen primary-care physicians had reached out and connected with psychiatrists, psychologists or other specialists, not only referring approximately 30 patients but following up about their care, said Benedict. About 20 or more of the Rhode Island Psychology Association members had used the network in October and early November, Oppenheimer said.

Benedict and Puerini see the network as something to be used beyond the corporation’s roster of primary-care physicians, since several health care leaders in Rhode Island have shown interest. •